By Kaitlynn "KJ" Johnson

Kaitlynn “KJ” Johnson is a current standing AmeriCorps VISTA member serving at Greater Portland Health, with background studies in Communication and Philosophy.

The act of vaping (or Juuling) suddenly and quickly integrated itself within the normative dynamics of daily life, predominately among youth. Attempts to understand youth vaping habits have received international attention, posing a challenge to all physicians. While personal reasons to begin vaping may vary, studies have recognized one trend in particular that is deserving of serious attention: vaping as a form of reducing stress.

Many health professionals believe this is due to the misconception that vaping is a healthy alternative to smoking cigarettes. While the ingredients used to make up E-liquid may include less containments than those used in cigarettes, vaping still imposes its own unique and harmful set of health consequences.

As of 2019, 45% of Maine’s high school students and 16% of middle school students have vaped at least once, and the number of youth choosing to self-medicate through vaping continues to rise. As a result, vaping addiction among this age group is already high and is continuously getting higher.

It is no secret that there are several social determinants imposing stress and anxiety on the younger generations of today, including the high expectations they are asked to meet. It is valid to feel stressed no matter who you are; it is even natural to want relief from stress. While the research around vaping is still new, there is enough definitive information to arrive at this conclusion: Vaping is not a healthy coping mechanism for stress. Vaping may actually further initiate and worsen one’s stress over time.

Jennie Yamartino, a Licensed Clinical Social Worker and the Social Worker Supervisor at Greater Portland Health, speaks on her experience working with youth who vape and how it directly impacts their levels of stress and anxiety:

“Vaping is common among the high schoolers I see for counseling. One student in particular has been open about what he describes as his addiction to vaping, which began when he was in the 6th grade. He shared that prior to vaping, he did not struggle with anxiety, but that once he began, he felt anxious ‘all the time.’ He only felt calm when actively vaping – and when he was unable to, it was all he could think about.

“It impacted his schooling, relationships with family and friends, and sense of self. His classmates would tease him for how often he vaped. He shared that he began to hide his vaping not only from his family, but also from his friends. He became more isolated and felt alone.

“As an 8th grader, he decided that he wanted to stop vaping – and successfully quit. As a high school sophomore, he said it was the hardest thing he has ever done, but also one of his proudest accomplishments. His advice to people who are thinking about trying it: ‘Don’t even start [vaping]. It may be fun when you’re doing it, but hurts you a lot in the long run.’”

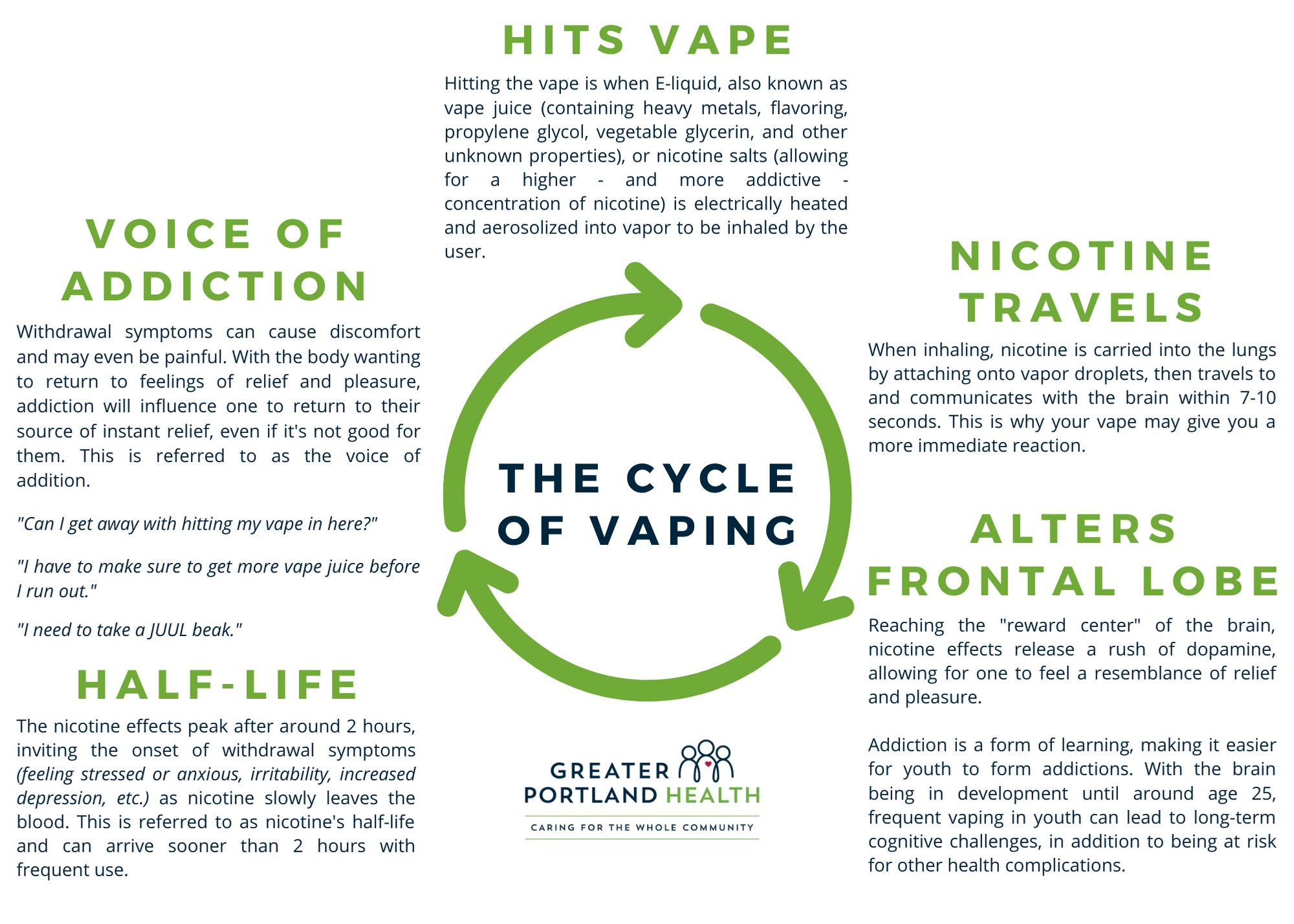

To better understand how vaping can have these quick and drastic effects on a person, particularly teens and adolescents, it helps to examine the Cycle of Vaping:

Hits Vape

Hitting the vape is when E-liquid, also known as vape juice (containing heavy metals, flavoring, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and other unknown properties), or nicotine salts (allowing for a higher - and more addictive - concentration of nicotine) is electrically heated and aerosolized into vapor to be inhaled by the user. A 100ml bottle of E-liquid can contain as much as 3,600mg of nicotine. That is up to 100x more nicotine than a pack of cigarettes and 25x more nicotine than a can of smokeless tobacco.

Nicotine Travels

When inhaling, nicotine is carried into the lungs by attaching onto vapor droplets. From there, nicotine travels to and communicates with the brain within 7-10 seconds.

Alters Frontal Lobe

Nicotine interacts with one’s frontal lobe, also known as the reward center of the brain, releasing a rush of dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a huge role in our ability to experience pleasure by communicating with other neurons throughout the body. The quick reaction between nicotine and dopamine is what offers a temporary sense of “instant relief” or “instant pleasure” for the user.

It is important to note that addiction is a form of learning, making it easier for youth to form addictions. With the brain being in development until around age 25, frequent vaping in youth can lead to long-term cognitive challenges, like memory loss, inability to concentrate, and impaired decision making—in addition to being at-risk for other negative health complications.

Half-Life

Nicotine’s reaction in the body peaks after 2 hours on average, inviting the onset of withdrawal symptoms (feeling stressed or anxious, irritability, increased depression, nervousness, etc.). This is known as nicotine’s half-life, and can arrive sooner than 2 hours with frequent use.

Voice of Addiction

Withdrawal symptoms can cause discomfort, and in some cases can even be painful. With the body wanting to return to feelings of relief and pleasure, nicotine addiction will influence one to return to their reliable source of instant relief, even if it is not good for them. A common way this happens is through the voice of addiction, the voice that tells someone to keep vaping.

“Can I get away with hitting my vape in here?”

“I have to make sure I grab more vape juice before I run out!”

“I need to take a JUUL break.”

By understanding how nicotine and the act of vaping can trick the mind and body into feeling reduced levels of stress, we can begin to better equip ourselves, and our communities, with the necessary resources that offer the support required for achieving long-term relief, while also preventing future negative health complications.

By bringing this information into our conversations with friends and family, we allow ourselves to get honest about vaping habits in youth, its relationship to stress, and how we can work together to eradicate this epidemic.

If you or someone you know is struggling with vaping habits and would like additional support, Greater Portland Health recommends contacting the Maine QuitLink. The Maine QuitLink offers phone coaching, web coaching, and individual services for vaping and smoking recovery. They have the tools to support someone whether they are ready to quit or just thinking about it.

Enroll online by visiting mainequitlink.com, or by calling 1-800-Quit-Now.

If you are a patient of Greater Portland Health, you can call 207-874-2141 and our staff will assist in referring you to the QuitLink Services.

References

“Anxiety, Stress, and Vaping.” Smokefree Teen, teen.smokefree.gov/quit-vaping/anxiety-stress-vaping#:~:text=Stress%20and%20anxiety%20can%20trigger,deal%20with%20stress%20and%20anxiety.

Miller, Stephen, et al. “Negative Affect in at-Risk Youth: Outcome Expectancies Mediate Relations with Both Regular and Electronic Cigarette Use.” Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, U.S. National Library of Medicine, June 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6938030/.

“Nicotine - Understanding Addiction and Potential Harms.” MaineHealth Center for Tobacco Independence , ctimaine.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Nicotine_Understanding-Addiction-and-Potential-Harms-Infographic_final-9.11.19.pdf.

Raven, Kathleen. “Teen Vaping Linked to More Health Risks.” Yale Medicine, Yale Medicine, 18 Dec. 2019, www.yalemedicine.org/news/teen-vaping.

“Resources: Tobacco Control Network.” Tobacco Control Network Resources Comments, tobaccocontrolnetwork.org/resources/.

“Vaping and Depression Go Hand-in-Hand.” United Brain Association, 1 Dec. 2020, unitedbrainassociation.org/2020/02/04/vaping-and-depression-go-hand-in-hand/.

“Why Teens Choose to Vape: Dr. Roseann & Associates.” Dr Roseann - Neurofeedback, Evaluation & Therapy, 30 Sept. 2019, drroseann.com/psychology-of-vaping/.